Historical Memory, Human Rights

Monsignor Romero’s funeral

(ORIGINALMENTE PUBLICADO POR CARLOS DADA EN EL FARO)

On March 30, 1980, Palm Sunday, Romero made his last trip to the Cathedral. His body, in a gray coffin trimmed with silver, was carried in procession from the Basilica of the Sacred Heart by a dozen young priests and accompanied by bishops from across the continent. It was his funeral.

It was not a royal funeral. Not a single member of the Governing Board or the cabinet attended to salute the archbishop. Neither did Army officers or most of the diplomatic corps. There were no gala cadets to guard the coffin, nor were gunshots sounded nor did representatives of the private sector appear. Not even all the member bishops of the Salvadoran Episcopal Conference were there. In contrast to his pompous beatification in San Salvador, held 35 years later, that March 30 Monsignor Romero was honored by the people, who turned en masse to honor his greatest defender. The number of people — between 100,000 and 150,000 people — expressed popular devotion to the archbishop, given widespread suspicions that the funeral could be used by the extreme right or the extreme left to unleash pandemonium.

Rumors had reached the military leadership that groups of guerrillas were planning to infiltrate the march and steal the coffin containing Romero’s body. The Salvadoran church, alerted to those alleged plans, decided to celebrate mass in the atrium of the front steps of the Cathedral and keep the iron gates closed to serve as a separation between the dead and the crowd.

José Napoleón Duarte, the Christian Democratic leader recently returned to the country after a long exile in Venezuela, had joined the Governing Board a few days earlier. Everyone, military and religious, knew that groups of guerrillas would enter the plaza accompanying the funeral, Duarte wrote in his memoirs. “The Church knew that guerrilla delegations would arrive at the funeral and they asked them to arrive last at the plaza… The military wanted to stop the guerrillas but I advised them to leave the funeral alone.” Duarte attributes himself to having convinced the military “not to fall into a trap”, to avoid being provoked by armed groups in front of television cameras around the world. The Army was quartered.

Cabinet members were also to stay out of it. Romero’s assassination was already a major problem for the government. Any provocation at the funeral could trigger a tragedy and a political crisis for the weak government.

(…)

One hour before noon, according to the chronicle of the Spanish newspaper El País, some 150,000 people were already in the Cathedral and its surroundings (La Prensa Gráfica spoke of 50,000). The Archbishop of Mexico, Ernesto Corripio Ahumada, appointed by Pope John Paul II to preside over the funeral, began the services around 11:30 in the morning, accompanied by the apostolic nuncio, Emanuele Gerada, and two dozen bishops from several countries in North America, Europe and Latin America. In front of them, still open, the silver coffin with the remains of the murdered bishop.

Fifteen blocks away, in Parque Cuscatlán, in front of the Military Hospital, thousands of people summoned by the Coordinadora Revolucionaria de Masas—a kind of umbrella organization for popular movements—began their march toward the Cathedral. Several of the protesters were armed. This was the march that everyone feared. They went down Alameda Roosevelt shouting revolutionary slogans and entered Plaza Barrios at the corner of the National Palace and the Cathedral. Their march contrasted with that of hundreds of national and foreign religious and nuns who, with their robes on, made a pilgrimage singing along Second North Avenue. The religious entered the square at the corner of the National Theater. On the other side, on the corner of the National Palace and the Cathedral, the Coordinator’s demonstration entered. The square, which was already bursting with people, immediately noticed their arrival. Banners and megaphones stirred up those already there. The crowd greeted them with applause and cheers. The crowding in front of the Cathedral was already huge, under a suffocating sun. Relief corps gave help to more than one person who had fainted.

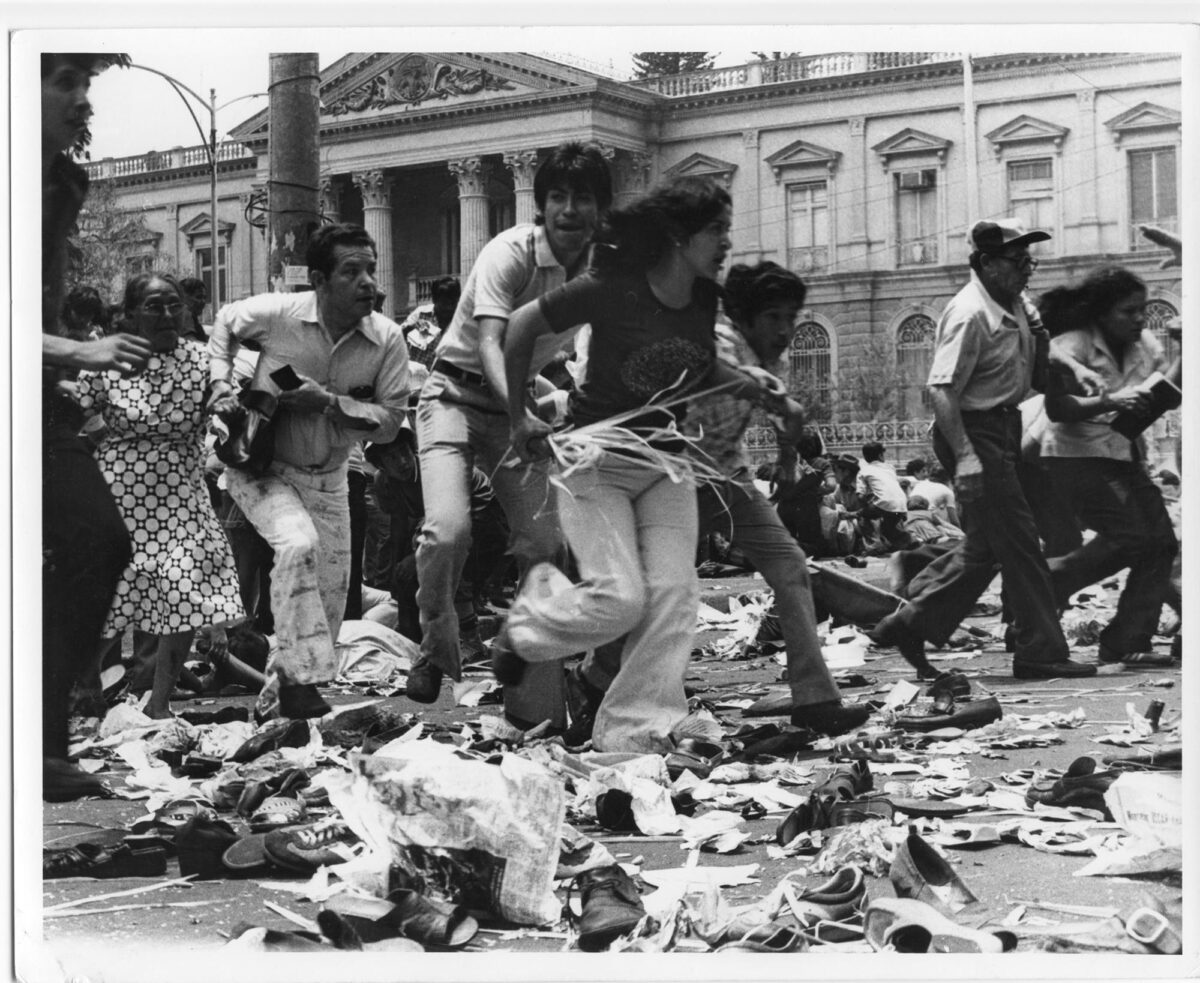

There are several videos of what happened next, but it is impossible to determine where the first shot came from or what those detonations were. In the images, religious sing and popular organizations shout slogans. A first explosion is heard. People next to the National Palace run in disarray, with their backs to the building, which indicates that the first detonations took place there. But from inside the Palace? Above? From outside? The rest of the crowd, bewildered, flee in confusion. To anywhere. Just run away.

Juana Lemus (an attendant) claims to have seen armed people in the Palace. One of the bullets fired from the balconies, she assures, hit Amílcar González, her 18-year-old neighbor who kept weapons in his house and whom she saw arrive with the Coordinator’s march. She too saw him vanish into the square. He was the first to die.

According to New York Times correspondent Joseph Treaster, the first explosion was at 11:40 in the morning. Immediately afterwards there were “rifle shots followed by rounds of semi-automatic fire and more explosions”. In the middle of all that the stampede originated.

Juana Lemus was still in front of the Cathedral gate when the chaos began. Men and women ran over each other. Tripping was fatal. She decided not to move. She clung to the perimeter railing as hundreds scrambled to reach the temple steps. Some protesters drew their weapons and fired into the palace or into the air or who knows where. Against who knows what. Those with megaphones tried to calm a crowd that had no ears for anyone. “Get down on the ground, don’t run, stay calm”, can be heard in the audios.

There was no more ceremony. The religious who surrounded the coffin with monsignor’s body carried it into the temple. Outside, rivers of terrified people streamed toward Plaza Morazán and the National Theater and down the other side streets. Several were crushed to death in the stampede.

Juana Lemus did not let go of the railing even when the woman who was next to her, and with whom she had been talking before the uproar began, told her to run, that they were going to be killed there. “No”, Juana Lemus replied. “I stay here”. The lady ran to the National Theater. Juana Lemus squeezed the railing between her hands and lowered her head. She stayed like that until there was silence in the square. There would be a long time before that.

After the gate was forced, thousands took refuge in the Cathedral. Armed civilians, who accompanied the Coordinator’s march, rescued the wounded and transferred them to the temple. Others, with their faces hidden behind scarves, pointed at the National Palace. But who was shooting from the Palace?

In the square there were still thousands of people who, immobilized by panic or serenity, remained at ground level, face down, barely showing their eyes to prevent danger. The videos recorded the panic: mothers running, dragging their children by the hand; first responders moving the wounded with makeshift stretchers. Peasants holding their hats while trying to run crouched. Explosions are frequent. It is impossible to distinguish in old and damaged images the dead from the living. In the middle of the square, a photographer leans the camera over a lifeless body that serves as a trench. On the ground, a man in dark glasses, who appears to be in his thirties, holds a cigarette between his lips. He smokes, with a calm that contrasts with the panic around him. His right hand holds a pistol.

American priest James L. Connor was by the coffin when he heard the first explosion. With all the other religious, he took refuge in the Cathedral. Behind him, protesters broke the locks on the railing and entered. “I saw the terrified mob force their way through the gates and occupy every inch of the temple. I looked around me and suddenly realized that apart from the nuns, priests and bishops, the other mourners were the poor and marginalized of El Salvador.”

Bishops and priests, guided by Corripio Ahumada, lowered the coffin and buried it quickly in the hole dug in the basement of the Cathedral to serve as a tomb, where it still remains today. There was no time for ceremonies. Just a couple of sentences. A troubled Irish Bishop Eamon Casey helped carry Romero’s coffin to the spot. Still shaken by the tragedy around him, he would tell a journalist minutes later: “There is something very vile on this earth. Very, very vile.”

The explosions and shooting continued for another hour and a half to two hours. People sheltering in the church huddled under pews or huddled together. Between the crowding and the fear, and the heat of that day, it was getting harder and harder to breathe. Men continued to enter from the plaza carrying the bodies of dead people.

After one in the afternoon, Nuncio Emanuel Gerada called the authorities and demanded guarantees that the clergy and all the people who were in the Cathedral could leave without fear of attack or arrest. When he got them, they all came out with their hands up. That day, almost 40 people died, most crushed; and more than 200 were injured.

Juana Lemus survived. Miraculously she didn’t even have a scratch. She just lost, she didn’t know how, her shoes. A few years later, her group in the San José de la Montaña church was dispersed after receiving threats from extreme right-wing groups. Someone convinced her that the Catholics were turning into communists and that they were going to kill her, so she, Juana Lemus, became an evangelical. A pastor promised her that if she brought her husband to her temple, she would help him overcome alcoholism. And he made it. Her husband died sober in 2012. Her son, the soldier, was discharged from the Army at the end of the conflict and today works as a private security guard, earning $152 a fortnight.

(…)

Clinging to the railing, (Juana) saved her life. She does not know why, when the fence fell, she did not go into the Cathedral to take refuge. As if she had passed out on her feet, she stopped noticing the noises around her. An hour later she opened her eyes and saw the bodies lying in the square. Dead. She walked barefoot. No hurries. She headed for the National Theater and there she saw, at her feet, the body of that lady who told her to run to save her life. Dead. Crushed. Next to her, also dead, a child. “That’s where the war began for me,” Juana Lemus tells me now… That day she continued to walk barefoot unperturbed by the burning asphalt… She did not stop walking until, near the Central Market, she ran into her husband and her son, who were leaving the cinema. Together they returned home.

The war had begun.

Read the entire article (in spanish) and watch the photos here.