Defending Natural Resources, Human Rights

Two pandemics in Jiquilisco

(ARTICULO DE GLENDA GIRON ORIGINALMENTE PUBLICADO EL 26 DE ABRIL DE 2020 POR “SÉPTIMO SENTIDO”)

In developed countries, Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is related to pre-existent conditions, such as diabetes or hypertension. It means that the deterioration of the purifying function of the kidneys comes as a consequence of the previous failure of other processes. In those countries, it is a disease that represents a serious health problem from the point of view of research and diagnosis. It implies, for patients and for health systems, a treatment that is complex and expensive. In these countries, avoiding this situation requires promoting, mainly, the control of excesses, such as sedentary lifestyle or diets high in fat and sugar.

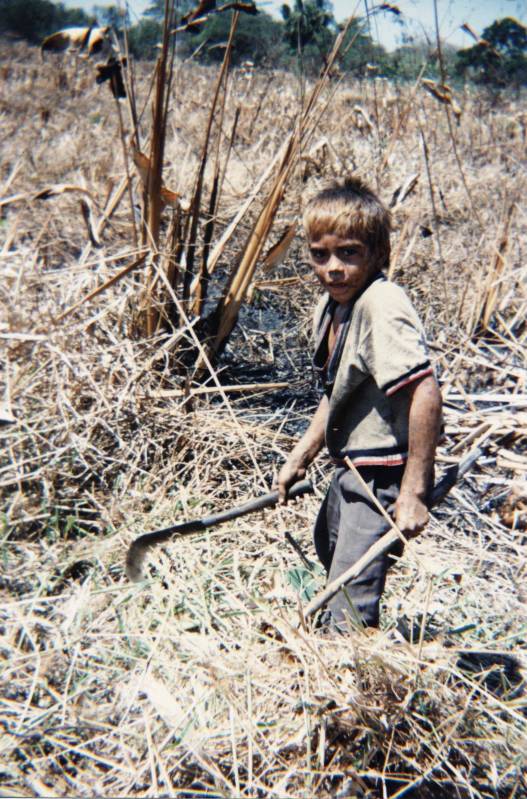

Julio Pérez lives in El Salvador. In his house – with dirt floors and made of sticks and plastics – there is the same kidney disease with the same consequences, but it has an origin that has nothing to do with abundance. Kidney disease in developing countries prevails in farming communities, among the poorest population.

Julio is 41 years old and no longer remembers how old he was when he started working. One does not pay attention to such dates in this rural area of Jiquilisco, on the coast of the Usulután department, in the eastern Salvadoran area. Here, in the very rural village Roquinte, almost all economic activity is agriculture or fishing and there is not a set age to start.

“I worked carrying bricks, in the mangrove swamps, collecting ‘curiles‘ (crabs), in masonry and in the cornfield, and quite a bit in sugar cane fields” he says. The list of what Julio has cultivated is varied, and the same applies to the amount and type of chemicals that he has had to apply or to which he has been exposed.

The disease that has been advancing in the municipality of Jiquilisco for two decades is the same one that has been devastating agricultural communities in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama. It is known as chronic kidney disease from non-traditional causes and is, like macrocultures, rooted to the depths of communities on the Pacific coast of this region. This other kind of impaired kidney function is very different from what is reported in the United States or the United Kingdom. Our kind finds its causes in environmental pollution, limited access to drinking water, inadequate working conditions, contact with agrochemicals and, more importantly, poverty.

For Carlos Orantes, one of the nephrologists who has been dedicated greatly to conducting international research on this disease, the classification that CKD for non-traditional causes, judging by its geographical component, has been clear for years. This professional, who in 2009 began directing studies in the Lower Lempa area (to which Jiquilisco belongs) points out that this is not an “individual” phenomenon, it is a “population” phenomenon and, because it is present in more than five countries, maintaining similar characteristics, should be recognized as a pandemic. “But we are used to relating the phenomenon of pandemics only to transmissible diseases”, he explains. Transmissible are those that are passed from one human being to another by means of vectors, like what happens with the covid-19.

In terms of distribution of medical services, Jiquilisco belongs to a micro-network in which facilities such as health units and hospitals are coordinated. This is where the nephrologist Denis Calero works: «In the five years I have been here, this has always been the micronetwork with the highest prevalence of CKD in the country; and it is both for the number of already diagnosed cases that we handle and for the new ones that are appearing», he explains from his position as director of the Community Unit for Specialized Family Health “Monsignor Oscar Arnulfo Romero”.

Jiquilisco, with the CKD, is already fighting a decades-long battle against a disease that counts among its risk factors another of the great problems for the inhabitants of this coastal municipality: poverty, which is present in 44.5 of households, according to a report of the Human Rights Office. These are homes like the one Julio shares with his wife, mother, and other family members. They live in an adobe house that barely stands up and is next to a ravine through which murky waters pass. Santos is Julio’s mother and she says that she was able to buy this land through loans that she paid, little by little, with the money left by selling tortillas.

Now, to this already precarious reality we must add the threat of contagion of covid-19. Here it is not only about viruses and tissues. It is about physical and social vulnerability. CKD places its sufferers at higher risk of complications from covid-19. And poverty places people at a disadvantage in terms of food availability, resources to travel to collect medicine, and even access to basic services such as clean water in their homes.

«For us it is complicated. In the hospital they give us the material, but last time we went to fetch it, it was crowded», explains Julio from a corridor where a hammock hangs. He remembers that there was nowhere to sit and what saved them was that their mother, Santos, carried a pair of plastic seats. «There we were lending them to other older people, that’s how it goes», Julio recalls as he stands leaning on his crutches.

In Julio’s words, as a user of the health care network, the main instruction that has been issued by the Ministry of Health is confirmed: that CKD patients be given the supplies to continue performing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis at home. Julio must, every four hours, walk to the only room with a brick floor and covered walls in the house. This space was built by the family, with much sacrifice, and is reserved exclusively for him to undergo his treatment.

Dr. Calero, in his health unit, has sought to shorten the path for patients and has continued making tours to bring care. He acknowledges: “We are taking very strong measures against the coronavirus, but perhaps we are neglecting these patients who suffer from this other disease that has been here for a long time and is also one of the leading causes of death on a national scale”.

Limiting to the renal unit of which he is in charge, Dr. Calero confirms that, so far during the mandatory quarantine, three people have died from complications or progress of CKD. Three victims of pandemics overlapping.

IN EL SALVADOR, FOR 20 YEARS, the advance of CKD for non-traditional causes has been unstoppable. Between January and December 2019, for example, 5,133 patients with CKD were diagnosed, according to the evaluation report of the Institutional Operational Plan made by the Ministry of Health. All were found in stage 5, this is the advanced stage, it is when people are one step away from depending on substitution therapy treatment.

Of these cases discovered last year, only 10% had access to substitute therapy, as the same report acknowledges. Only 544 of those more than 5,000 could have access to dialysis or hemodialysis. And these numbers are partial, since Rosales National Hospital, one of the hospitals with the greatest capacity to diagnose and care for kidney patients, was not included in this measurement.

The hypotheses that have been raised about the causes of CKD suggest that it is multicausal and includes among its factors issues that are social in nature. “The disease is caused by occupational exposure to agrochemicals, used indiscriminately and without protection during agricultural activity and by environmental exposure to contaminants in the soil, water, air and food”, reads the 2015 National Survey of Noncommunicable Diseases. It continues:

“Such exposures are enhanced by intense work activity, carried out under high temperatures and inadequate hydration and associated with social determinants, mainly poverty.”

On his table, Julio has a bottle of alcohol gel and is wearing a mask. Santos, Julio’s mother, explains that 14 years ago, when he presented the first symptoms, the first thing they thought was that he was mad. Fevers made him delirious and his behavior was seriously affected.

In 2004, the scientific and government discussion about CKD in farming communities was just beginning. Farmers and their families deteriorated and died in a matter of weeks, months at most. Dialysis and hemodialysis treatments, which replace kidney function, were barely known in the community. Julio was afraid of such treatment. “He acquiesced because at that time four of the neighbors died, one after the other”, Santos recalls. For 12 years he has been on ambulatory pericational dialysis, which means that every four hours, he is confined to his sterile room and, there, he is connected to two hoses: liquid enters one and leaves the other.

Julio has seen not only coworkers die. He has also seen his neighbors die from the same illness that affects him. Just as four died when he first learned his diagnosis, throughout his treatment many more have passed. There have been so many that he doesn’t even remember.

The premature mortality rate of Chronic Kidney Disease in El Salvador grew 3.3 points in just one year. For 2019, it reached 56.3. In this country, this disease kills more people than cervical cancer or hypertension.

Julio, like other of his neighbors who are also sick, does not have any other condition, only CKD. According to the Non-communicable Diseases Survey, of all CKD cases detected in El Salvador, in 30% of them hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or albuminuria are absent. The risk factor for which 30 out of 100 people suffer from CKD has more to do with where they live, the conditions, the climate and the type of work they do.

Jiquilisco already appears as one of the municipalities where covid-19 cases have been reported and have been classified as local. The virus, which is highly contagious, is already circulating in the community.

Due to the risk of covid-19, CKD patients have been highly encouraged to stay home. Consultations in the intermediate units are suspended, to avoid crowds. They want that the patient does not leave their house. They have invited family members to collect the supplies on their behalf. But this measure of containing patients in their homes is also a condemnation, considering the quality of the properties that most people suffering from CKD can pay in areas like those in Jiquilisco.

In El Salvador, 75% of the housing stock has some deficiency in its quality. Among the weakest, there are 3.5% that do not meet the minimum requirements established as acceptable for a home, according to the “State of Housing in Central America” report backed by Habitat for Humanity, among other institutions.

***

Santos, Julio’s mother, in fact, admits that she bought the land where they live even after she was warned that it had already been sold to someone else before her. Thus, they belong to that 24% of families living in houses whose property is not safe. And, taking construction materials into consideration, 25% of the Salvadoran housing stock has a deficient roof, walls or floors. Julio stands on a dirt floor.

Covid-19 and CKD have one recommendation in common: handwashing. Like many other illnesses, personal hygiene works as a barrier. With covid-19, to avoid contagions. With CKD, to avoid infections. Here, however, it must be taken into account, too, that 27 out of 100 households report problems with the water supply.

In Jiquilisco, Dr. Calero indicates that in the Renal Health Unit he is in charge of, he receives from 600 to 800 patients. They are at different stages of the disease. But it is worrying that some of them are in stage 5 already depending on therapy, either on home dialysis or on hemodialysis in a hospital center. They must be treated. “There is fear among patients of going to a hospital or health unit, due to this quarantine. For a patient of kidney disease, this is serious. If we do not see them at their appointments, it can get complicated, the patient can develop serious uremia or they can end up with pulmonary edema“. The doctor, in one day, organized home visits to eight patients distributed among villages which are not easy to reach. He did it as his own initiative, which he considered viable due to the number of patients he has in this serious condition.

***

The Ministry of Health has not issued a special guide for patients with CKD or for those who suffer from any other chronic non-communicable disease, except, the general one, staying at home to reduce the possibility of contagion.

In an article that this newspaper (La Prensa Gráfica) published a couple of weeks ago, Dr. Carlos Orantes, a nephrologist and researcher, already explained the risk this population is at: “Patients undergoing dialysis are particularly vulnerable to this coronavirus, especially those who do not receive an adequate dialysis dose“, he explained. The reason, he continued, is “that it affects an already diminished immune state which increases the risk of presenting the most severe form of covid-19”.

Julio knows he must stay home. But the circumstances in which he and his family must comply to this measure escape any social media cliche. There are no books here, no series and streaming services, no home delivery either. Santos, Julio’s mother, stopped making tortillas and now her daughter-in-law runs the business. They all live of what she sells. Selling every day is, however, a risk itself. By the time that traffic restrictions intensify as has happened with other municipalities, there will be no more customers. There will be no income. There will only be themselves, in their adobe and tin house trying to survive two pandemics.

Originally published on April 26, 2020.