Sister Cities

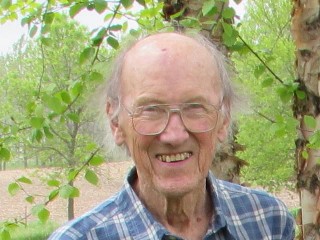

¡Presente! Art Lloyd Remembered

ARTHUR LLOYD

December 5, 1927 – August 4,2015

The Reverend Arthur “Art” Selden Lloyd moved to Madison, Wisconsin, in 1968. Over the next decades, Art played a key role in developing several of the solidarity initiatives that ultimately gave rise not only to the Madison-Arcatao Sister City Project, but also the U.S.-El Salvador Sister Cities network, and a still-expanding web of sister parishes and companion congregations.

“I had my eyes opened by the Civil Rights Movement in the ‘50s and by the anti-war movement” of the 1960s, Art explained in a 2001 interview. Between 1961 and 1967, he worked in campus ministry at Indiana University (IU), Bloomington. Because he was on campus, he said, he learned about the organizing activities of the socialist-inspired Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a national organization that was highly critical of the United States’ Cold War foreign policy as well as the structural violence at home that contributed to racial discrimination and economic inequalities. “That was really my eye-opening experience,” recalled Art, “hearing these young students talk about what was going on in Vietnam and U.S. policy and the corporations.”[i]

These experiences provided a context which helped Art “to be much clearer about what was going on in terms of Latin America.” Art began engaging directly with Latin America as early as 1961, when he and Sue, whom he had married in 1960, and two IU students traveled to Brazil. There they accompanied companion churches in their work, traveled, and learned about the lives of ordinary people in a society on the brink of upheaval. A few short years later the Brazilian Armed Forces carried out a coup d’etat, initiating a brutal military dictatorship that lasted until 1985.

When Art moved to Madison in 1968 to become the Episcopal chaplain at St. Francis House, he carried some of his Brazil connections with him. Presbyterians in campus ministry at Cornell University, who had been working with companion churches in Brazil for years, invited representatives from three other universities with solid global studies programs to an important meeting around 1970. Faculty, campus ministry personnel, and a large number of graduate students from the Universities of Wisconsin, Texas, and California joined their counterparts at Cornell to determine how to respond to feedback they had been receiving from their colleagues in Brazil: “Don’t bring your students down here. Go back home and do your work at home.” Out of the Cornell meeting came a plan to establish, Art said, “little community campus organizations that would try to use the resources of the campus and the campus ministry connections to the churches… to develop educational programs around what was going on in Latin America and what was the U.S.’s involvement.” This was a kind of “missionary in reverse,” Art explained, “where the object is to educate the U.S. and develop a constituency that would support changes in policies.” The Wisconsin attendees, including Art Lloyd, returned to Madison to form Community Action on Latin America (CALA). CALA quickly rose to national prominence by hosting two large conferences: the Non-Intervention in Chile founding conference in 1971 and, in 1974, the Conference on Repression and Development in Brazil and Latin America, which historian James Green points to as the beginning of a “qualitatively different phase” in solidarity work with Latin America.[ii]

Art continued to help organize and maintain CALA for years, obtaining office space and funding to support part-time staff so that the organization could continue to work on “whatever Latin America issues came up.” By the late 1970s and early 1980s when Central American issues began to take center stage, CALA was well-poised to take a leading role in the solidarity movement. In fact, it was an active CALA member who initially raised the idea of Sanctuary in Madison and in April 1983, with the support of some 15 congregations, St. Francis House Episcopal Church, where Art had been chaplain until 1977, became the first church in the area to declare Sanctuary for Central American refugees. Other churches followed and, in September 1986, Governor Anthony S. Earle proclaimed Wisconsin a Sanctuary State for refugees from Guatemala and El Salvador.[iii]

In addition to CALA, Art was instrumental in the formation of other prominent Central America solidarity efforts, including the Dane County Religious Committee for Central America (DCRC) which emerged in 1983 after the Reagan administration’s invasion of Grenada and met monthly “to educate ourselves.” He was a local coordinator of the Pledge of Resistance, a nation-wide network of people who pledged to engage in civil disobedience if the Reagan administration moved toward direct intervention in Nicaragua. And, most important to sistering, he was a founding member and long-time “convener” and “sort of president,” as he put it, of the Wisconsin Interfaith Committee on Central America (WICOCA).

WICOCA emerged around 1983 as a way to coordinate solidarity efforts on a state-wide level. The group lead information-gathering delegations to El Salvador and Nicaragua, promoted public education events throughout the state, and pressured local, state, and national politicians to adopt more humane policies toward Central America. As displaced and exiled Salvadorans began returning home and repopulating rural communities in 1985 and 1986, WICOCA took the lead in developing accompaniment projects. Working with the Wisconsin Conference of Churches, the local Sanctuary community, CALA, and other local groups, as well as national organizations like the Interfaith Office on Accompaniment and the New El Salvador Today Foundation (NEST), WICOCA led dozens of delegations to accompany Salvadorans on the journey home from refugee camps in Honduras, deliver moral support and material aid to repopulated communities, and to gather information about human rights violations committed against the repopulators.

It was out of WICOCA’s El Salvador Accompaniment Project that the Madison/Arcatao Sister City Project (MASCP) was born. Those involved with accompaniment developed a sistering proposal, which they presented to Madison’s Common Council in early 1986. That April, the Council formally pronounced a Sister City relationship with the town of Arcatao, El Salvador. Over the next couple of years, local activists from CALA, WICOCA, and Sanctuary collaborated with NEST to develop and grow the Madison/Arcatao Sister City Project. By 1988 MASCP had become a full-fledged organization with staff, office space, and hundreds of supporters. And today, as we know, MASCP continues to grow in its sister relationship with Arcatao.

WICOCA promoted many other sistering connections as well. Working with MASCP, for example, WICOCA “facilitate[d] the linking of farmers from three rural Wisconsin communities with the Salvadoran community of Arcatao.”[iv] Beyond Arcatao, WICOCA worked with Salvadoran Humanitarian Aiad, Reseach, and Education Foundation (SHARE) to set up “sister relationships between faith communities [in Wisconsin] and in the repopulated communities of El Salvador.”[v] By the end of the 1980s, two Catholic parishes in the greater Milwaukee metro area had sistered with the Chalatenango communities of Guarjila and Ignacio Ellacuría. This gave rise to a Milwaukee working group and more formal collaboration with the Archdiocese of Milwaukee “to develop a program of sister parishes with El Salvador to deepen the faith life of parishes here and to join the Salvadoran churches and communities as they have worked to end the war and, now, reconstruct their communities.”[vi] Shortly thereafter Lake Edge Lutheran in Madison and St. Sebastian Catholic Parish in Menomonee Falls had partners in Chalatenango, the Greater Milwaukee Synod of the ELCA had a “sister synod” relationship with El Salvador’s Lutheran Church, and working groups continued to reach out to parishes, congregations, and synagogues across the state. In short, reported WICOCA’s Board of Directors in April 1992, “This work is thriving.”[vii] Recent interviews reveal that the work is still thriving, with a thick web of parish relationships linking the Upper Midwestern states of Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Illinois with communities across El Salvador.

These interrelated layers of sistering work, inspired in large part by Art Lloyd’s vision and leadership with WICOCA, made Wisconsin a “national leader” in Salvadoran refugee support and “civic foreign policy-making,” in the words of one journalist.[viii]

Art Lloyd continued to be involved with MASCP throughout his life. He and Sue first traveled to El Salvador in 1989 with several teachers and a load of school supplies. They returned in 1994 to observe the first post-war elections, and then again for elections in 1997. For years, the Lloyds have been safely storing the MASCP archive while we search for a permanent home for it. They Lloyds graciously (and often) shared their experiences with me since the late 1990s, when I first began researching the history of MASCP. In late May, they both took time to attend the monthly MASCP “core group” meeting even as they prepared to hop an early morning flight to Cape Cod.

We are honored to have Sue Lloyd with for this National Gathering. Art is with us too. He is here in spirit in this room. And his vision of peace and justice lives on in the many people — young and old — he worked with and inspired in campus ministry, CALA, WICOCA, MASCP, and elsewhere. Those folks — like me — will continue the hard and wonderful work of building a more peaceful, just, and equitable world.

— Molly Todd

[i] These and subsequent quotations from Art Lloyd are drawn from Molly Todd, interview with Art and Sue Lloyd, 12 Mar. 2001, Madison, Wisconsin.

[ii] James Green, “Clerics, Exiles, and Academics: Opposition to the Brazilian Military Dictatorship in the United States, 1969–1974,” Latin American Politics and Society 45, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 109. Dozens of folders from these conferences have been archived with the Records of Community Action on Latin America at the Wisconsin State Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin (hereafter WHS).

[iii]“Wisconsin a Sanctuary for Refugees,” Washington Post, 21 Sept. 1986, A5.

[iv]El Salvador Accompaniment Project of WICOCA, “History and Context of Project,” 7 Sept. 1988, Records of the Madison/Arcatao Sister City Project, private collection, Madison, Wisconsin.

[v]The WICOCA Sister Community Project, n.d., Records of the Wisconsin Interfaith Committee on Central America (hereafter WICOCA Records), Box 1, File “SHARE – Sister Parish Program,” WHS.

[vi]Eric Popkin to Archbishop Rembert Weaklund, 2 Mar. 1992, WICOCA Records, Box 1, File “Origins of WICOCA,” WHS; WICOCA Board Meeting Minutes, 6 Aug. 1990, WICOCA Records, Box 1, File “Board Meeting Minutes,” WHS.

[vii]The WICOCA Sister Community Project; Mary Kay Baum and Loretta M. Grow to friends, 20 July 1994, WICOCA Records, Box 1, Folder “Origins of WICOCA,” WHS; WICOCA, “History…”; WICOCA Board Meeting Minutes, 21 Apr. 1992, WICOCA Records, Box 1, File “Board Meeting Minutes,” WHS.

[viii]WICOCA, “History…”; Eric Scigliano, “Sisterhood,” New Republic 207 (1992): 12–3.