Defending Natural Resources, Sister Cities

El Salvador: Mining the Resistance

“Ultimately,” said Miguel Rivera, a soft-spoken man in his late 20s, “we are a family that has dedicated ourselves to helping the people with their needs and defending their rights. But in the process of denouncing the consequences of mining especially, I think there are people that will be your enemies.”

Rivera, a director of the Asociación de San Isidro Cabañas (ASIC), a human-rights based community organization in San Isidro, El Salvador, spoke from personal experience. Last June, his brother—and colleague—Marcelo went missing after a series of death threats linked to his opposition to gold mining in the region. A few weeks later, his body was found in a well, stripped of his fingernails, scalp, nose, and mouth.

Despite repeated calls for justice, police never performed any investigation into the intellectual authors of the crime, and Marcelo’s turned out to be the first in a series of activists attacked that year. His murder was followed by two more assassination attempts in coming months, and then by the killing of two more anti-mining activists during the last week of December. Ramiro Rivera Gomez—who survived an attempt on his life in August—was shot in his car on December 20, and Dora Alicia Recinos Sorto was gunned down six days later as she returned from washing clothes at the river. Several other activists have narrowly escaped similar assassination attempts; even more have been moved into safe houses; and a few dozen have received personal death threats via e-mails and text messages throughout the year—all, so far, with relative impunity.

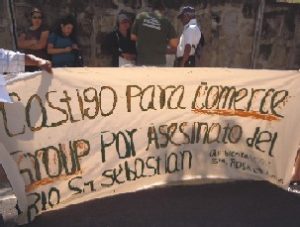

While the authorities have yet to identify the intellectual author of the crimes, however, friends and colleagues of the victims know who is roughly behind the intimidation.

“There is a company, Pacific Rim, interested in starting a mineral exploitation of gold and silver at El Dorado,” said Chico Montes, director of the local human-rights organization la Asocación de Desarrollo Económico-Social (ADES), speaking of a site in the San Isidro municipality. “The ministry has given them an exploration permit. And imagine the interest of those people who want to appropriate the wealth. So the explanation of the threats comes from there.”

The Canadian-owned Pacific Rim Mining Company has attempted to exploit a gold mine at El Dorado for the better part of a decade, and has been repeatedly thwarted in their efforts—not least due to the resistance of organizations like ASIC and ADES. Now, apparently, the company’s local allies have taken a more violent approach to removing that opposition.

“I believe it’s a campaign of intimidation, and of course the same people are implicated in all of it,” said Rivera. “They want to destroy the entire resistance.”

Allegedly, Marcelo’s murder was carried out by four gang members who were reputedly paid $100,000 each for the task. As an activist in San Salvador pointed out bluntly, “you don’t need half a brain to know who has that much money around here. It’s the company.”

E-mail threats sent out late last year even came from an address whose alias was “exterminio pacificrim.”

“To me, if you connect the dots from Marcelo to Don Ramiro, it’s very clear,” said another activist, who wanted to remain anonymous out of fear of retribution. “Those are two of the people who have had the most violence carried out against them, and they’re both in key mining areas. So why has Pacific Rim not said anything? Why are they not calling for investigations into these murders and attacks?”

Pacific Rim, for their part, did not answer phone calls to that question.

**********

The mining story starts in the 1990s, when the Salvadoran government bowed to World Bank pressure and reformed its tax code to encourage foreign investment, including mining. El Salvador had never been a mining capital, but as strains of gold and silver were discovered throughout the region companies began entering the country. In 2002, Pacific Rim acquired a project in San Isidro—a municipality in the northern Cabañas district of the country—known as El Dorado, and received a exploration permit to determine the mine’s potential. The explorations revealed an incredibly valuable mine—estimated to be worth $3.3 billion in 2007, when gold prices were under two thirds their current price. In 2004, Pacific Rim filed for a permit to exploit the mine.

Metallic mining throughout El Salvador, however, came under increasing attack from non-profit groups throughout the country, who argued that the mining activity would lead to widespread contamination of the surrounding environment and water supply—as it had in neighboring Guatemala and Honduras. Pacific Rim and the other mining companies denied these claims, but political sentiment quickly swung against the foreign corporations. Increasing numbers of community organizations came out against it; eventually the Catholic Church followed suit. The government dragged its feet on the permit, spurred on by a February 2007 letter signed by several NGOs and 41 U.S. Congresspeople. Finally, in March 2009, even the country’s right-wing then-president Antonio Saca came out against the mines. Several other mining companies in the country became discouraged and left the country; Pacific Rim followed suit, at least temporarily, in July 2008.

Five months later, however, Pacific Rim filed a notice of intent to sue the government of El Salvador for failing to provide the exploitation license and comply with the terms of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). (Because Canada is not a signatory to the treaty, Pacific Rim brought litigation through an American subsidiary.) The suit, which began on May 31st and calls for damages of $77 million, will ultimately determine whether El Salvador can legally prevent mining within its own borders.

In the meantime, however, the debate over mining is being carried out in an entirely separate—and much more local—arena. Pacific Rim has spent the last several years trying to achieve what their company literature refers to as their “social license” in the country—“earning the respect and approval of local stakeholders.” To that end, the company invested in a range of social programs in Cabañas, spending $1 million in 2007 alone on community social initiatives.

But to many in Cabañas, “social initiatives” is not an accurate description of these projects, which are often administered independently by local mayors.

“The group in power in our department is the right. So, Pacific Rim supported some politicians with money for projects,” said Oscar Beltrán, a producer for the community radio station Radio Victoria, which often broadcasts anti-mining messages. “And it is a way for the company to control the mayors.

“If I give you two million dollars for you to invest in the projects you want, and tomorrow I ask you to do something, you’re going to do it,” he explained frankly. “This is the role currently being played by several mayors in the department of Cabañas.”

It is not just the current largesse of the mining company that has won over some mayors in the region. Because Salvadoran law taxes corporate profit 1% at a local level and 1% at a federal level, the municipality of San Isidro would see its budget increase tenfold—to $1 million—if the project went through. The result, say community leaders, is a unified front of local right-wing politicians and Pacific Rim.

“Why does someone go looking for a post as mayor?” asked Miguel Rivera, rhetorically. “It’s a way of making money.

“Around here, the mayors—more than mayors, they are activists for the mining company,” he added.

It would hardly be the first indiscretion on the part of mayors in Cabañas. Last January, several NGOs uncovered evidence that the politicians were committing widespread electoral fraud. On election day, Marcelo Rivera and ASIC found a number of Hondurans (Cabañas is right on the border) who said they had been paid $100 to come across the border and vote for thirteen-year mayor of San Isidro José Ignacio Bautista. Similarly, Radio Victoria reporters came across a group of Hondurans waiting to get DUIs—the identification card that allows Salvadoran citizens to vote—in Sensuntepeque, another city in the region.

According to Miguel, ASIC was preparing a campaign to reveal the truth when their office was raided and their direct evidence was lost. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the local government did not investigate the robbery.

Because of ASIC’s actions, many in the area suspect that Bautista was the one who directly ordered Marcelo’s murder. At any rate, Bautista is not the only implicated mayor.

“Here, at least four mayors from ARENA are related to this sort of thing,” said Montes, referring to the right-wing party which is one of two major parties in the country.

And mayors are not the only figures who were wooed with Pacific Rim money; according Beltrán, some local churches even started taking money from Pacific Rim. Eventually, however, the Church nationally came out against mining, and the priests cut off ties with the company. Indeed, national political sentiment has almost exclusively turned against mining. But, as the assassinations and intimidations suggest, Pacific Rim has not given up the battle for local influence.

“Pacific Rim has invested more than $28 million in this country,” said Beltrán. They’re not going to want to give it up that easily.”

**********

Luis Quintanilla, an outspoken leftist priest, very nearly became the second person killed in 2009, as he returned home on July 27 from his weekly radio program on Radio Victoria.

“Monday, the 27th, I came to the radio at night,” said Quintanilla, a youthful man with a thick beard. He explained that he was cut off on the road back to Sensuntepeque by a car that had been following him. With the road blocked, Quintanilla stopped his car.

“Then they opened the door,” he explained. “They told me to turn off my lights and leave the keys in the car. When I got out, I closed the door and locked it. They carried me towards their car. There were two of them—one on each side—and another stayed by my car, and another was driving, so they were four. All dressed in black, hooded, and armed. And one, that was next to me, was saying ‘leave him to me here,’ and I understood that they were going to kill me. But the other said ‘no, we’re supposed to take him with us.’ They couldn’t agree if they would do it there or if they would bring me somewhere else.

“And then in my car, the alarm went off. The one that was on one side of me went over to the car, and the group went to see what was going on, and I dove away. There was a ravine there—I didn’t know there was a ravine there, I just jumped.”

Quintanilla landed on his hands and knees, and then ran until he was sure the men were not following him; there he called friends, and soon paramedics and police arrived at the scene. The investigation that followed, however, was far from encouraging.

“That same night, the police arrived,” he continued, “and they said, ‘Well, did they hit you?’ And I said, ‘no.’ They looked over the car, and they asked, ‘Did they steal from you?’ And I said, ‘no.’ ‘And this dent on the car that you have here—you already had it?’ ‘I already had it.’ ‘Well, then,’ they said, ‘they didn’t hit you, they didn’t hit your car, and didn’t steal from you? Then nothing happened. If you want, you can bring charges. If not, nothing happened.’ And I said, ‘How is it that nothing happened? They were about to kill me.’ But they said no.”

Quintanilla, who has been involved in social projects since his days as a student in the 1980s, began doing radio programs when he was suspended by the Church in 2002 for his political views. He began attracting the ire of conservative forces in the country, he said, when he got his job back through the courts in 2004. A couple of years later, he received an anonymous message which said: “Since you like to talk so much about Monseñor Romero and Father Rutilio Grande, we will make sure you go and keep them company.” (Romero and Rutilio were outspoken populist priests who were assassinated in the years before the Salvadoran civil war.)

The day after the attempted kidnapping, Quintanilla went to the district attorney’s office where, due to those threats, there was already a case open on his behalf. But the attorney refused to connect the previous night’s incident to that case.

“The attorney said to me, ‘given that since the noted date nothing has happened’—which is to say, that they haven’t killed me—‘we’re going to close the case,’” said Quintanilla. “I said ‘no, on the contrary, I want you to continue, since things are still going on.’ He told me ‘Fine, but that would be a new claim.’”

Quintanilla’s was not the only case of Orwellian justice during the year. When Radio Victoria asked the local police for officers to protect the radio station and its members after repeated death threats, they were informed that there were not enough police officers available. (The national police ultimately supplied one officer for each of the six or seven people directly threatened, leading a national newspaper to hyperbolically report that an army of sixty officers was protecting the radio.) Earlier in July, police reported that Rivera had been murdered when a fight broke out between him and a group of gangsters he was drinking with—despite the evident signs of torture on his body and the fact that Rivera did not drink.

El Salvador has been controlled by an often-corrupt right wing for over three decades, despite a twelve-year civil war beginning in 1980. Last March, a candidate from the left-wing FMLN (the party established by the guerillas in the 1992 peace treaty), Mauricio Funes, finally won the presidency, bringing hope to the long-disenfranchised left-wing resistance that the government might finally be accountable to them.

In Cabañas, however, the political switch has gone in the opposite direction; for the first time in years, all nine municipalities in the region are controlled by ARENA. And the control of the municipalities, naturally, carries over into the justice system.

“Of course, the district attorney doesn’t investigate anything because the district attorney has blood on his hands,” said Montes. “They are interested in justifying. They’re not interested in investigating.”

“There has been a change in the government, but at the base, here in the department, there has been no change,” said Edward Lara, a manager for Radio Victoria, who received a series of personal threats via text message throughout July. “It’s still like the time when the right was in the government.”

Radio correspondent Isabel Gámez likened the situation to the overtly violent days leading up to and during the civil war—a war in which many of the older activists fought as guerillas.

“These are things of the past—the persecution, the assassinations of people who are in positions of power in the organization,” said Gámez. “It’s like going back in time. We’re regressing.”

Since the murder of Ramiro and Santoro in December, there were signs that the status quo could change; President Funes himself made a public declaration connecting the latest murders to the events of the summer, and promised a full investigation.

Whether Funes can navigate a national police force and justice department riddled with corruption, however, remains to be seen.

“I’m somewhat hopeful, but at the same time I’m afraid,” said Quintanilla. “Not afraid for what might happen to me—afraid that we might fall into the same game, the same system that we have had for twenty years and even more.”

**********

“Marcelo was a person whose life was dedicated to two things,” said Miguel Rivera, speaking of his brother. “One was the work of social organization, and the other, perhaps, was being a political leader. And that is essentially what he did.”

Marcelo and Miguel—who had “always been a team,” as Miguel put it—began their organizing work when Marcelo was 18, and Miguel 12. As students, they recognized that there was no good way to access information in San Isidro. “You would need money to go to Sensunte or Ilobasco, because there was not a cultural center, or any place to inform yourself,” said Miguel, referring to two cities roughly a half hour away. “We created a San Isidro foundation for culture and art. It was a group of around twelve young people from 12 to 18 years that wanted a space to get information, and also an organization for cultural and artistic work in the municipality.”

“Marcelo was a person who liked art very much,” said Montes. “I remember that we contracted him, as ADES, so that he could conduct theater workshops with the youth in Santa Marta. And later, we realized that he had political sympathies too.”

Marcelo and Miguel eventually moved their work to ASIC, an organization “dedicated to supporting youth, and asserting the rights of the population,” said Miguel. The organization also addresses “issues of health, wells, people’s access to water,” he said.

In this capacity, organizations like ASIC have come to oppose the project of Pacific Rim. Extracting gold requires enormous amounts of cyanide, and El Dorado is located near the Río Lempa, which provides water for much of Cabañas and for San Salvador. The activists fear that the mining project will end in a catastrophic contamination of the water supply—and they point to precedent in Honduras, where mining indeed caused cyanide contamination, not to mention massive deforestation. Their widespread slogan—seen on stickers, posters, and pamphlets—reads “no a la minería, sí a la vida” (no to mining, yes to life).

Pacific Rim, which promises to meet or even exceed stringent environmental regulations in all of its mining projects, denies these allegations. Their executives say that they will be so carefully monitoring the water the mine discharges that the local streams may well be cleaner after the company begins operations at El Dorado. Also, notably, the toxic mines in Honduras were open-pit mines, unlike the underground mining that the company would employ at El Dorado.

Unfortunately, there has been no independent assessment of the environmental impact of mining at El Dorado, leaving the actual debate largely in the realm of rhetoric. Allegedly, various government ministers began working towards producing independent assessments in 2007 and 2008, but, as of today, nothing has come of them.

Objective depictions of Salvadoran public opinion on mining have been equally hard to come by. Pacific Rim cites a January 2008 poll which showed 67% of respondents supporting mining in some capacity, and only 30% entirely opposed. On the other hand, a survey conducted a few months earlier by the University of Central America found that 62.5% of respondents were opposed to mining in El Salvador.

Pacific Rim also argues that the department will greatly benefit from the creation of hundreds of sustainable jobs—no small benefit in an underdeveloped region. It is unclear, though, how long-term jobs could be connected to a mine that does not operate for more than a decade.

At any rate, the debate itself has not been incredibly rooted in much but rhetoric. With the conflict headed for international legal resolution, an empirical answer to the social and environmental impacts debate may be in the offing before any definitive study can address the question.

**********

Radio Victoria, a roughly 30-person operation run largely by youth from the area, is based in a plain two-story cement building on the main street of Victoria, a quiet city on a hilltop. In the entry room, photo collages commemorating each of the radio’s 17 years hang on the walls, along with a photo of Monseñor Romero doing a radio broadcast. (One radio member laughed that “a whole bunch of people” ask if Romero had been on Radio Victoria, which was founded over a decade after his assassination.)

“It was the end of the war, it was a time of transition, and it was very important for the community to have its own communication,” said Cristina Starr, an expatriate of the United States and one of the radio’s founders, thinking back on the radio’s origins. “And it’s appropriate technology because you don’t have to be able to read, and you can listen to the radio while you’re doing anything. It accompanies you.”

While the radio has no professed ideology or political persuasion, its accountability to the community has made it a central forum for anti-mining messages for several years, and has made it a target for the mining company and its allies. As early as 2006, several members of the radio’s news team received death threats. In 2007, Pacific Rim attempted to buy out the radio themselves.

“We were having problems constructing our house. We were partway done, and Pacific Rim said, ‘look, we can finish constructing your building easily. And it’d be better if you’d like us to. And on top of that, we can give you another $8,000 a month.’ So that we’d gave them publicity,” said Beltrán.

“And we said, ‘look, better that the house remain unfinished, that we never finish constructing it.’”

In mid-summer 2009, the radio found itself at the center of a storm of threats and sabotages. By mid-July, three community correspondents for the radio had been taken from their homes and put in safe houses after repeated threats left in voicemails and letters. Within the next two weeks, five members of the radio’s news and production teams received direct personal threats, and the entire organization received a long e-mail that named several more. The radio’s transmitter was sabotaged or stolen on several occasions, leaving the radio off the air for days at a time.

“There were two straight days of threats and more threats,” said Gámez, who was one of the most directly affected. One day in early August, as she was alone at the radio office preparing for a 4:00 news dispatch, she received a phone call from a person who claimed to have been at her house the previous night, and who said he was now waiting for her outside. After a frantic series of phone calls to friends, other organizations, and the police, Gámez escaped the building, and she and her family were taken to a safe house.

“It felt like things were getting out of control,” said Starr, “and you really felt like there were these dark forces there that were descending.”

While some of the threats lightened up after a few weeks, fears were reignited after Ramiro’s assassination when several members of the radio received an e-mail from “exterminio pacificrim.” “Well, we sent two into a hole, the question is, who will be the third,” read the message. “We prefer that the third death be a radio announcer or a correspondent or whoever from this damn radio, the most secure target is an on the air announcer, be careful, we are not playing.”

Several days later, six armed and masked men appeared outside Gámez’s house; ultimately, nothing happened, but only because Gámez was visiting family and not at home.

Despite the fear, Starr thought there was a silver lining in the threats. “It means that the radio really is carrying out its role,” she said. “I think that the important thing is to see it in the context of the social movement in Cabañas, which of course is connected to the larger social movement in El Salvador.”

Quintanilla, too, connected the intimidation to a bigger picture.

“The threatened ones are not just the individuals themselves. We see this situation as an attempt to decapitate the social movement,” said Quintanilla. “What they do is cut off the head. Yes, we are the focus, but it’s not just against us; rather, it’s against all the people with us.”

**********

On a Friday afternoon last August in Santa Marta, a village of 3,000 people half an hour from Victoria, a group of teenagers was collecting near the main plaza. Having finished classes for the week, they were waiting for a truck that would carry them to Victoria, where they would spend the night—keeping watch over the Radio Victoria building, which faced threats of arson.

“At the same time that it’s been scary, it’s been so moving to see how people from Santa Marta have responded,” said Starr. The delegations—usually consisting of ten to twelve people—came to the radio every night for nearly four months. In that way and many others, the threats at the radio have revealed the strength of the organizing spirit in Cabañas.

“I’ve talked to some of the youth like Oscar and Jaime and I go ‘are you scared?’” said Starr. “And they say, ‘oh, yeah, I’m scared, but you know.’ And they say things like, ‘Well, you’ve got to die sometime, you know?’ It almost sounds flippant but they’re actually really sincere. They’re actually really saying, if we’re going to die at some point and we have to die for something…

“That’s how they see it, that’s the level of commitment and dedication. It’s not just a radio; it’s part of this whole movement.”

Asked about the future of the radio, none of the members hesitated.

“To close the radio, or to abandon the work that we have done up to this point would be to comply with the objectives of the people that are threatening us,” said Beltrán.

“We exist and we were born to defend the rights of the people, and that’s how we’re going to continue,” said Lara. “And if that involves risking ourselves, we only hope that the population supports us, and helps us to protect ourselves.

“Really, the fear is very great—as much personal as familial. Sometimes you’re here doing the work, and you’re thinking about your family, and that, any moment, something will have happened. But nevertheless, the thing is to continue, not hesitate in this, because it is a project that has greatly served the social, economic, and human development of the communities, the community organizations, and the empowerment of the people.”

“One must recognize that this project of protecting human rights is a project that some groups don’t like—one must recognize that,” said Montes. “And these economic and political groups will act, and they will try to shut up the voices of dissent. In the department we are very cognizant of this—but we’re not going to stop. We’re not going to stop. We’re going to keep doing our work, defending human rights, and denouncing the violence.”

{mosimage}